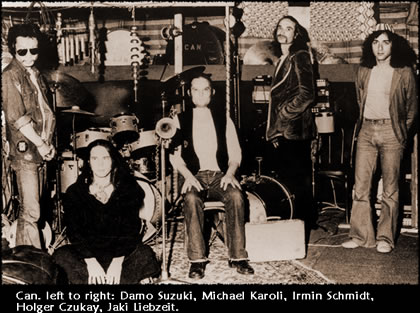

Holger

Czukay and Irmin Schmidt of Can interviewed by Damon Krukowski. None of

these people should need any introduction at all to readers of the

Terrascope, so we’ll dive straight in without further ado - starting with

Damon’s questions to Holger Czukay:

PT: Can had a genius for improvisation, and a genius for editing; how do

these two activities relate?

Holger Czukay: What we did was not improvisation in the classical jazz

sense, but instant composition. Like a football team. You know the goal, but

you don’t know at any moment where the ball is going. Permanent surprise.

Editing, on the other hand, is an act of destroying. And you should not

destroy something if you don’t have a vision to establish it afterwards. If

you have that vision you can go ahead and do that. Can was a band. The

editing had to handled carefully, because it could destroy the character of

the band.

PT: Is it true that there are hundreds of splices in the Can material?

HC: Yes. In my solo works there are sometimes thousands.

PT: Did the recording technology determine Can?

HC: Yes, very much. Not only the machines, but the studio itself. When we

built our studio, we were looking for a studio landscape. The separation of

control room and recording room is necessary only for conventional

recording. You must look for rooms or environments that have a certain

magic, and if they don’t have it, then you build it up. It’s the right

approach for inspired music making.

PT: To me the greatest change in the bands’ records came not with the

change in singers, but with the change to a multi-track machine on ‘Landed’

[1975] and following.

HC: Yes, there is a reason for that. We didn’t even have an engineer.

Everyone was responsible for the mix. And with the multi-track, this sort of

group responsibility was destroyed by the fact that -- of course everyone in

the group gets criticised -- but suddenly one could criticise in such a way

that one could say: it was the guitar. And then the guitar would get

paranoid, and do it again, and everyone else would maybe leave the studio

even, and suddenly this sort of single, out-of-the-group responsibility

happened. This was a big change.

PT: With just the two tracks...

HC: Everyone heard the mix in their headphones, and if one wanted to do

something to change what he played, he would destroy the entire product.

PT: Would you bounce the tracks?

HC: Yes, but we only did overdubs as a group, and only once or twice,

otherwise we were afraid of too much hiss. We were limited to copying it

twice.

PT: Why did Can become a rock band?

HC: By coincidence. None of us were rock oriented. But the only way to

become an entire group with a new sound, was to reduce ourselves. And when

you have a drummer like Jaki Liebezeit, who is more inhuman than a drum

machine... Jaki said we have to reduce ourselves to a minimum, and let

things run by themselves if possible. And he was right. Suddenly we became a

genuine sound.

PT: Did you ever use written music?

HC: No. Written music belongs to the past. It means: there is a creator, and

there is a performer. They are different people. And performers are

organised in unions... Stockhausen is a traditional composer -- innovative,

but a composer nonetheless.

PT: And Cage?

HC: Cage is exactly the opposite. Both worlds are possible and we are

somewhere in between.

PT: Is it true you once turned on all your instruments and left them

alone, to see what they would play?

HC: Yes. In fact the first Can concert with Damo Suzuki, that was how it

started. I found Damo in Munich, on the street. He came up singing and

praying to the sun -- very freaky. I said to Jaki, “This is our new singer.”

I said to Damo, “Who are you? What are you doing tonight?” He had nothing to

do, he was tripping around. “Would you like to sing? We are an experimental

group, we have a concert, and if you would like to sing, please come over.”

And he did. We didn’t have any rehearsal. It started with the instruments

alone, feeding back, and Damo was meditating, and all of a sudden he became

a fighting Samurai. And then a rhythm came up that was so unbelievable, that

the people got aggressive, and they all left.

Another time, I was working with David Sylvain. He came in the studio, and

we were having a chat together, and somewhere lost in the corner is a tone,

maybe from a radio or from an organ, and we became silent, and suddenly

there was this mystery, like a perfume, in this room, this studio. And he

got up immediately, and our first piece was done in one go. I am not a

technocrat.

PT: You believe in something magical?

HC: Yes. Tago Mago is a magical work. Before Jaki came to Can, he was trying

to commit suicide. He was playing with Chet Baker in Barcelona, as a jazz

drummer. Then he went to Ibiza. And south of this island is a rock called

Tago Mago. Mago means magic, and Tago was the name of a magic master who

lived there. And Jaki was on that rock and tried to spring down because he

thought his life didn’t make any sense. I think he is the one who said we

should call it Tago Mago.

PT: Do you write music?

Irmin Schmidt: When I started to make music, I wrote. But for a concept like

Can, you can’t write. This is obvious, because the author is Can. It is

creating on the spot.

PT: You studied with Stockhausen?

IS: Yes, among others. Ligeti was more important to my development at that

time than Stockhausen. Ligeti was a fantastic teacher. Not at all dogmatic.

PT: Was Can a break with those studies?

IS: Yes, it was. I was a conductor at the time: Webern, Schoenberg,

Stockhausen. At the time, there was a ban on improvisation. Boulez had put a

spell on any spontaneity -- there was all this very dogmatic thinking in New

Music. You had to have all this enormous complexity, with no repetition, and

no repetitive rhythms, and use every colour only once... all these rules

that didn’t develop very far because they were more the end of a

development, than the beginning of something. I wanted to go away from this.

I stopped conducting, and dedicated myself totally to Can. It was not that I

was at odds with the music, it was more the environment. I always did like

the music -- some of Stockhausen and Boulez and especially Ligeti.

PT: And Cage?

IS: Cage had an enormous impact. I met Cage when he made his first concert

in Germany ever, in Essen. I was totally amazed, I didn’t know what I should

think. I laughed -- you know, sometimes laughing is a reaction that frees

you. And there was this critic sitting behind me who got angry, and she

said, “If you find this funny, you should leave!” Then after the concert I

went to the dressing room, and this same critic was standing there talking

very seriously to Cage. And when she had finished I said, “Mr. Cage, you

must have seen me laughing down there, but please excuse me, it wasn’t meant

badly, it was just something that came out of my body without my willing

it.” And I explained that this woman standing beside him really felt bad

about it. And then he turned to this woman, he sort of took her in his arms,

and said, “Oh, didn’t you have any fun tonight? I am sorry!”

So I visited him a couple times, and he came and did another concert in

Essen. We had a drink before, and he said “Irmin, you can help me with the

performance tonight. I’ll tell you what to do right before it starts, I

don’t know yet what I want, but keep yourself available.” I told him where

to find me, in the gallery where all the professors were seated. And when

the lights went down, Cage came up to me and said, “Take this chair, and rub

it on the floor as hard as you can.” So I went with this chair through the

rows, and my professors thought I was going mad. I was the only one doing

avant-garde music there, so they already suspected I was mad, but now two of

them sprung up: “Irmin, what are you doing? The music starts at any moment!”

But of course the music had already started -- Cage appeared from the other

side, also with a chair, making the same noise!

And then one of them finally said, “Oh, I think this is Cage!” And they sat

down and stared at us. And the dancers from Merce Cunningham’s company were

there, they were all rolling on the floor... which at that time was not what

people imagined dancing was all about.

PT: So was meeting Cage very liberating for you?

IS: Yes it was. He was the most outstanding figure of this idea: that the

music is something around you, already existing. All you do is focus it. And

this is exactly how Can worked. We came into the studio, or on stage, or

wherever we made music, and it was our environment which created the music;

we were the media to focus it, to put it into existence.

I remember some tracks, like “Future Days,” where we came into the studio

and turned on the instruments, and the guitar was on the floor making a

strange sound on its own. Mickey wouldn’t do anything but let it make its

sound, and maybe move it to another place, where it made another sound.

Slowly everyone played with this sound, came into it, and we all created

from what was around us.

PT: To see what the instruments had to say?

IS: Yes. The piece “Unfinished” was made like this. When we switched on the

organ and the guitar, there was a strange interaction between them. The

organ was really broken, so when you touched one key the whole sound it made

changed. Even if you just approached it, it changed, because the waves

changed. So we thought, maybe we leave them alone for a while, and then come

back.

PT:

Why was Can a rock band?

PT:

Why was Can a rock band?

IS: We had to be, it was destiny. When we started, we knew we wanted to do

something spontaneous together. And it was necessary for music like this to

make sense to have a rhythm. It was Jaki who created the rhythm. And once

you have a rhythm, it became rock. And then one day, this friend of a

friend, a painter and sculptor who was a friend of the composer Tcherepnin,

we met in Paris, and we said, come visit us in Cologne. This was Malcolm

Mooney. When he showed up, I just said, come with me to the studio, we are

making music there. All of a sudden he took the mike and started singing.

And this was like the ignition -- this gave the last kick toward rock.

Between him and Jaki, who had already started to establish this hypnotic

rhythm, all of a sudden Malcolm directed all this undecided energy in the

group to this rhythm. He focused us all on Jaki’s rhythm. It was clear in

this moment that this is where we had to go.

PT: And you didn’t resist it?

IS: No, not at all, we embraced it! This was ‘Father Cannot Yell’, the first

piece.

PT: I don’t hear jazz in Can. However the concept of group improvisation is

very similar.

IS: Not really. Because we had nothing to start from. No theme, no nothing.

Only the environment, in the sense of Cage that we discussed. And this is

not jazz, this is something totally different...The one thing we had all in

common was listening to ethnic music. When we met we figured out that

everybody had listened to this -- I was into Japanese medieval court music,

Noh theatre music and Bugaku. Jaki was into Arabian music. And Mickey and I

were both big admirers of Balinese music, we were chasing after every tape.

PT: Did the minimalists interest you?

IS: Yes. In 1966 I came to New York for the first time. I was sent by my

professors for a conducting contest. But right at the start, I met Terry

Riley. He had this strange little grotto in the Bowery. We sat there night

after night, and he made me play “de dah de dah de dah de”... me on the

piano and him on the sax. At first I thought this was totally stupid. The

result was that I was thrown out of the contest, because I missed certain

rehearsals. I met Steve Reich, and he was also doing the “de dah de dah

de”... but he was different, he had just finished a tape-loop piece. I was

fascinated.

PT: Did you share Can’s music with these people?

IS: Yes, Terry visited us in the studio. Also I met LaMonte Young, and later

they had a concert in Cologne together with the Indian singer, Pandit Pran

Nath, and they visited us.

PT: Could they appreciate the ways in which Can spoke to what they were

doing?

IS: I don’t know how much they appreciated it, because their approach to

music was totally different. But they are very open-minded people.

PT: Minimalism was another way to reintroduce repetition and rhythm into New

Music, but I think the rhythms never got so interesting in that case...

IS: Basically, you are right, but I would say that with Steve Reich it is

different. I find pieces like ‘Music for 18 Instruments’ absolutely

wonderful, one of the highlights of this century’s music, and I find it

rhythmically enormously interesting. And that is written music, so that

returns to one of your first questions. I have no difficulty with any kind

of production of music, as long as the result is good music.

Written & directed by Damon Krukowski, Produced by Phil McMullen

(c) Ptolemaic Terrascope 1998