Blossom Toes

lossom Toes were the archetypal mid/late 60s English band: talented, imaginative, full of potential, mis-managed and ultimately ignored. In the following interview with big Toe Brian Godding, Steve Rowland removes the socks from the whole sordid tale... first though, the history bit.

Formed originally as a covers band circa. 1962 named The Grave Diggers by vocalist and (left-handed) rhythm guitarist Brian Godding and bass-player Brian Belshaw, who had met each other as apprentices at work in a scientific instrument makers factory in North London, after several line-up shuffles and with the mood of the times swinging towards RnB, they drafted in Eddie Lynch on lead guitar and Colin Martin on drums, changed their name to The Ingoes (after a Chuck Berry song of that name) and set about attempting to conquer the burgeoning London RnB scene. This proved unsuccessful until they managed to coerce club owner and Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky to take them under his wing, whereupon they were packed off to Paris for eighteen months or so to establish a name and a following for themselves. This they did quite successfully. Remarkably successfully in fact; their sound developed considerably, integrating a little soul into the RnB and at the same time becoming increasingly freaky, and they quickly gained a name as one of the hottest acts in Paris. After a short stint back in London, where they replaced Eddie Lynch with veteran RnB guitarist Jim Cregan, they returned to France to strengthen their stranglehold on the scene and spread their wings further into Europe.

The Ingoes returned to London in 1966, where Giorgio Gomelsky, no longer involved with The Yardbirds, revealed his new plans for the band. They were to be ensconced in a communal house in Fulham where they would write and rehearse for six months, eventually emerging with a new identity (Blossom Toes, a name thought up by someone at Gomelsky's Paragon agency) and with enough material written to record an album. Drummer Colin Martin left the band at this point and was replaced by one Kevin Westlake. After a period of total disorganisation (the band were to enjoy their new-found freedom to the full) the four of them - Brian Godding on rhythm guitar and vocals, Jim Cregan on guitar, Brian Belshaw on bass and vocals and Kevin Westlake on drums - started to craft a style and a collection of songs of their own, with Godding in particular emerging as a very fine songwriter in the quirky English tradition of Ray Davies and others of that ilk. They soon had enough material for an album, and went into the studios to demo the tracks which were eventually appear as their first LP, `We Are Ever So Clean' (Marmalade, 1967).

Gomelsky at this point decided, probably as a result of being heavily influenced by The Beatles' `Sgt. Pepper' which had just been released, to lavish orchestral arrangements on most of the songs - some of the tracks indeed weren't to feature Blossom Toes at all, aside from coming in to add vocals to the music being

performed by the orchestra and session musicians (this wasn't an unusual turn of events at the time, as witnessed in our Kaleidoscope interview of a couple of issues ago.) Having said all that the results aren't as bad as they might have been, and the album remains a real highlight of 1967 English psychedelic pop with a particular gem in `Look At Me I'm You' - one of the songs which does feature the band; others include `I'll Be Late For Tea', `Telegram Tuesday', `What On Earth', `Frozen Dog' and `I Will Bring You This And That'.

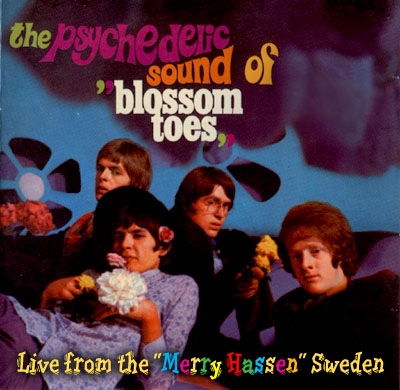

Having been buried for several months writing and recording, the Blossom Toes didn't actually play any gigs until the `Love-In' held at the Alexandria Palace in July 1967, where they played a foreshortened set due to the fact that the majority of the material from their album, as heavily orchestrated as it was, was virtually unplayable live. They then disappeared off to Sweden, where they played a three-week residency at Stockholm's leading psychedelic club, The Merry Hassan. Here they abandoned all hope of performing their established material, and progressed - as far as I'm concerned that's the right word - onto playing almost freeform noise with a heavy dose of Beefheartian influence chucked into the chemical stew. A bootleg exists of one of their shows there which reveal the band to have been experimenting freely; the material is almost unrecognisably theirs, with the exception of `Listen To The Silence' which was to turn up on their second album.

Their return to England was marked by another change in drummers: this time Kevin Westlake was replaced by Poli Palmer, a veteran of the Midlands scene (and a future member of Family, as regular Terrascope readers will by now have realised) who was not only a drummer but brought to the band his talents with the flute, Mellotron, vibes and other assorted percussion. The new line-up started writing material that could actually be performed, although their first attempt to record was a dismal failure - a cover of Dylan's `I'll Be Your Baby Tonight' (the reasons for which were down to Gomelsky's misguided attempts for stardom once again.) Their next single, `Postcard'/'Everyone's Leaving Me Now', was a much more successful outing though, and it bode well for the long-promised second LP.

Poli left the band shortly after the single was released however, and was replaced by Barry Reeves (late of a band called Ferris Wheel) and it was this final ingredient which finally brought the Blossom Toes to the boil. Godding moved up to lead guitar, and it was with this twin lead-guitar front of Godding and Cregan that the band went into the studios in 1968 to record their new album - the fabulous `If Only For A Moment' (released on Marmalade again, in 1969). No orchestras this time, just four musicians in total command of their material. `Peace Loving Man' is the real standout - a dynamic, acid-drenched guitar workout written by Godding and sung by Belshaw (and with Poli Palmer on drums; it was in fact the last thing Palmer recorded with the band. Reeves overdubbed congas afterwards) - but others, like `Listen To The Silence' and `Kiss Of Confusion' are of equal standing. A stunning album, and one which should have brought them the success they so richly deserved.

Things weren't to be however, and despite major successes on the Continent the Blossom Toes - or at least, the two Brians - decided to call it a day in December 1969. They had simply had enough.

Godding and Westlake formed what was effectively a new Blossom Toes out of the ashes of a film-recording project later in 1970. Calling themselves BB Blunder, they recorded one album (of the same title) which is for me the real highlight of the whole Blossom Toes oeuvre; more `progressive' in keeping with the times, it nevertheless captures their songwriting and playing at its very best. There was however to be one footnote to the Blossom Toes as a band. They appear together as such on one track of Julie Driscoll's excellent solo album `1969' (released on Polydor in, surprisingly enough, 1970). The connections between the Blossom Toes and the Brian Auger/Julie Driscoll circle go back some way - they had all appeared at the `Love In' at the Ally Pally in 1967 for example - and it's from that angle which we are approaching the following interview with Brian Godding, for reasons which will become clear when you reach the credits.

Brian Godding himself is still probably most widely known (aside from his Blossom Toes involvement) for his collaborations on sister-in-law Julie Driscoll's (now Tippetts) albums and the fact that he has been Mike Westbrook's lead guitarist of choice for the last twenty-odd years. He's still going strong, gigging and recording with his own jazz-flecked band, Full Monte, who are well worth checking out if you get the chance. A genuinely gifted guitarist, he is also very modest about his talents and speaks eloquently and enthusiastically about still getting a real buzz from composing and playing music - all of which will become apparent, I hope, from the interview which follows.

PT: Can you remember what first got you into playing the guitar?

BG: Yeah, I can actually. George Formby, when I was a kid. I didn't start by playing the guitar, I actually started by playing the ukulele. I can remember that more vividly than a lot of stuff that's happened more recently. I was fascinated with that noise Formby used to make on the banjo. I think he was quite a heavy-duty guy, actually, a bit like Norman Wisdom. He was great when you were a kid, but as you get into these people you find they can be quite tyrannical.

So you picked up the ukulele...

Yeah, basically. My dad used to work for the GPO, he got an old earphone from a telephone and stuck it in the little hole in my ukulele, believe it or not, and he actually wired it up - so I had an electric uke when I was about six! I doubt that anybody else had electric guitars then, but you could plug this electric uke in the back of the old valve radio. I used to sit there strumming away.

And guitar influences?

It's got to be the Shadows and the Beatles. That's what drove me into wanting to play that particular instrument. I just became attracted to it through their music. I still think they sound great, in fact. Unlike a lot of their contemporaries who sound dated now, I can still listen to the Beatles and wonder how the hell they did it, especially with the recording techniques at the time. They were pretty special and fortunately they remain so.

So when did you start to play guitar with other people? Were you in a school band?

No. I didn't actually start playing guitar till I was about sixteen. I was working when I got my first guitar. I was doing an apprenticeship at a scientific instrument making firm in Highbury, North London and Brian Belshaw was working there. We just kind of drifted into playing. There was another guy there called Alan Kensley who was playing the guitar and he used to bring it in and I just eventually ended up getting one and joining in with them, so I didn't actually start playing the guitar until I was quite old - sixteen or so. But as soon as I got involved, it all happened quite quickly. I think there was about four months between my picking up a guitar and leaving my apprenticeship. I absconded to Soho and was living in a place that belonged to Brian Belshaw's uncle's business. We were just basically kipping on the floor of this greengrocery shop. It was great - it's great fun when you're that age.

Was that The Ingoes?

It was, or at least it became The Ingoes. In fact it was called The Gravediggers to start with and we used to do Screaming Lord Sutch tunes like `Jack The Ripper'. Brian Belshaw's got this really gruff voice and used to do a really good impersonation of Sutch.

Who else was in The Ingoes apart Brian and yourself?

We needed a lead guitar, because I was rhythm guitarist, so we got a guy called Eddie Lynch in and we spent quite a lot of time working with him. Then we had a drummer called Colin Martin, who's now working as a radio producer. I don't remember where we met the guys but when the band solidified it stayed together with that line-up for a year, quite a long time in those days (1965).

How did you first connect up with Giorgio Gomelsky?

We weren't playing blues music as such but we were interested in it, so we kept pestering Giorgio because he was running the Crawdaddy clubs at the time. We used to go and see these bands like The Yardbirds, what have you, and we'd pester him to try and get some work. Anyway, eventually he took us under his wing and promptly sent us off to France where we lived for a year or so in Paris and that's basically where we improved and became a band.

Your equivalent of the Star Club!

Basically, yeah - except the French have got a lifestyle which is not like the German or the English. We made a lot of friends out there, people whom I still consider to be good friends even twenty years later. Quite a few people looked after us very well. So that's how we met Giorgio, it was through his clubs. We ended up working at the Crawdaddy clubs quite a lot, supporting bands like The Yardbirds, The T-Bones. It was a good time.

Did Gomelsky try and record any

of your early stuff? I know he dragged people like

The Yardbirds and Sonny Boy Williamson into the studio on

occasions.

Did Gomelsky try and record any

of your early stuff? I know he dragged people like

The Yardbirds and Sonny Boy Williamson into the studio on

occasions.

We weren't considered to be a very viable proposition then, just a prospect. He thought "one day these boys might be doing something". But we did back Sonny Boy. Sweet old sod, he used to come over here, totally alcoholic, and we used to do all these London suburbs with him. We'd just go down and play twelve-bars and he'd get up and wail away on his mouth-organ. It was interesting. It was interesting to see a guy who knew exactly what he was going to do and it didn't make the slightest bit of difference what we did at all! (Much laughter)

So you paid your dues for a while and then you became Blossom Toes.

It was Giorgio's marketing bunch in his office at Paragon who came up with that idea. They decided that The Ingoes wasn't a good name, so they came up with Blossom Toes and we went along with it because it meant that we could get in the studio and make an album. The name seemed very unimportant at the time; the impor

tant thing was the getting into the studio, so basically we went along with much of what was thrown our way. That first album was our songs but the actual recording was out of our hands. If you know the record you'll know there's a lot of orchestra on it. At the time we didn't want to do that for two reasons: one, we would rather just have played the songs ourselves because that's how we wrote them and rehearsed them and two, we had to go in and perform with the orchestral musicians or string quartet or whatever - because of union rules and the fact that we only had 4-track machines. It all had to be done live, no overdubs, and it was quite intimidating for us lot.

Where was `We Are Ever So Clean' recorded?

That was done at the Chappell Studio down in Bond Street. It was a good studio. John Timperley was the engineer. He was a very, very good engineer. He was the saving grace, really, of the whole thing. He in fact pulled the album together. Giorgio was having a pretty bad time because of drink and if we'd had a lesser engineer that record may not have got made or it may not have got put out or it may have been bloody awful - which I don't think it is. It's not particularly representative of us at the time but I don't think it's a bad record.

Was it a conscious departure from the group's sound?

Yes, from the management's point of view. The idea was to chuck us onto the Beatles bandwagon, presumably. They were a company who wanted to exist and survive, so

they wanted bands that were successful. There was obviously a potential within the band to be sort of poppy, which we didn't particularly want to be, but then we didn't particularly not want to be. We didn't really know what it meant! If The Beatles were `poppy' then I suppose we would all have been quite happy to be that sort of band at the time. Like all bands, we got slung from pillar to post; they wanted to market us this way, market us that way. They didn't actually understand that the bottom line of it is four guys who actually just want to play. The rest of it is just a pose, you know.

I think your enjoyment of the playing still comes through on the record. It still sounds inventive and quirky and humorous.

Yeah, I don't think it's a bad record at all. To me it definitely sounds dated, you know, more so than the second. The second has group connotations.

It was Giorgio's idea to put in all those wacky little intros, was it?

Yeah, probably him and Jim, probably between the two of them and Kevin. There was a lot of humour in the band. People like Jim and Kevin were both quite humorous in their own ways. I wasn't around when that was done. I didn't even know they were going to do that.

In the end you didn't include much of `We Are Ever So Clean' in your stage show?

That's right. We couldn't play it like it was recorded, with all that orchestration, I mean we couldn't have touted an orchestra round

with us, so we just said forget it. I actually think they're fantastic people, classical musicians. I think they're completely misunderstood. People see classical musicians as very staid, scholastic people but in my experience I've found them to be almost psychopathic - I mean, talk about drinking! It's probably because of the strictness of what they do, but anyway when they've finished doing whatever it is they do they go absolutely apeshit. I really enjoy their company! They're very open-minded people, and very talented. Without them there is no music, just a lot of stuff written on paper. I think they're misunderstood people.

But you wouldn't have taken a bunch of them to Stockholm with you, for instance!

On one of our little sorties to Sweden? When we went out there the band was in a terrible state. Everybody was taking LSD and stoned and things. We went out to Sweden to do these gigs and quite honestly we didn't have any tunes. It was as simple as that. We just improvised and it was a shambles. That bootleg recording of us that's around is a terrible indictment of what we were like at the time, quite frankly. We went out to Sweden with twenty half tunes or quarter tunes or just titles or chord sequences with no words and that's what you're getting on that live record - plus the fact that everybody is completely out of their crust.

What about your cover of Dylan's "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight"?

It was crap! I'd put it in a league with Hermann's Hermits. It was a joke. We were a quirky sort of English band and trying to do cover versions of Bob Dylan was really stupid in retrospect. We were good at what we did, but not good enough to go round covering people's material like that.

When did you start recording the

material for the second album, which I think I prefer to

the first?

When did you start recording the

material for the second album, which I think I prefer to

the first?

Me too. I think it's a better record in as much as it represents the band and what people were feeling like at the time. There was quite a lot of thought went into that second record from our point of view, rather than from some arranger's point of view or some engineer's point of view. It was very much what the band wanted to do at the time so, for better or worse, that to me is the more important record.

Kevin was long gone by then.

Yeah. It was a shame in fact, because Kevin was an immensely creative geezer and it's a pity he wasn't still in the band when we were functioning like that.

You enjoyed making that second album, by all accounts.

Yeah. It was good fun to make. We had more control by then. Certain lines had to be drawn when you were working with Giorgio. By the time we were doing `If Only For A Moment' we'd come to some pretty clear understandings with that whole situation, with Paragon and Marmalade and Giorgio in particular in that we weren't really interested in making another album unless we could make it the way we wanted to - which

is what we did. Julie (Driscoll) came down and did a few things with us. It was much more of an open situation. We felt that we came out with a band record, basically. We'd contributed to the production as well as the music and we were happy that we could go on stage and play all those tunes. That's what Blossom Toes did until the day it packed in, was went out and basically played that album.

I didn't realise that Julie Driscoll contributed to "If Only For A Moment ". She's not credited.

I think she sang on `Hobby Horse's Head' and it was certainly at a Blossom Toes recording session that she hit Giorgio with her handbag, very hard on the head. Several times!

Do you remember playing support to Jefferson Airplane at the Roundhouse in 1968?

I don't, actually. I used to go home after our sets at the Roundhouse because I lived just down the road! I remember supporting Captain Beefheart in Cannes. That was bloody good fun. They came over and they didn't have any equipment so they borrowed all ours. Talk about out of their heads! I didn't believe anybody could be that stoned and still be alive! Kevin used to love their stuff but I was never that keen on it myself, to be quite honest. I hate slightly out of tune guitars, I really can't abide them. I'm not talking about cacophony or discord, I don't mind that, it's just things that are quarter tones and eighth tones out of tune. I don't like it.

Is it true that you

played on Brian Auger/Julie Driscoll's `This Wheel's On Fire'?

I didn't really play on it - I just put a bit of mellotron on at the end. That was done while they were mixing. Brian wasn't there. He didn't seem to mind. But it was nothing. I wasn't sitting there playing with them - I wouldn't even attempt to play a keyboard with Brian Auger around!

Did you play on anything else that the Trinity did?

No. We were never really around at the same time. Because they were touring pretty constantly at that time, we didn't see an awful lot of them, but having said that I got on very well with Brian. The whole band were extremely nice people. In fact, when The Blosses split up Brian was so cut up he actually gave us £200 (which was a lot of money in those days) to go away for two weeks to think about what we were doing. He didn't think we should split up.

Why did Blossom Toes fold?

Belshaw and I left. We just got fed up with it, to put it in a nutshell. We'd been a band for quite a long time as The Ingoes and Blossom Toes and I just wanted to get off the road, to get out of it. We rolled our Volkswagen van on the way home from a gig in Bristol one night in December '69 and that put the band off the road for a couple of weeks, during which time I just decided that I'd had enough.

There was rumour at one time, after Julie left Brian and the Trinity, that she was going to join up with

Blossom Toes.

Well, she was interested in what we were doing, so she used to come down - and when the Blosses split up as well, it was the natural thing to think about doing things amongst ourselves. She wanted to do more English-type stuff rather than all the things she'd been doing, and obviously the idea of Julie singing with us, or some combination of us, was great. We thought she was a great singer. We did some things together. She sang quite a lot on the BB Blunder record.

You backed her on the "1969 " recording as well.

During the "69" thing the Blosses were still more or less together, but in name only. It was understood that we'd never be going back out on the road again.

So you folded Blossom Toes and eventually resurfaced as BB Blunder. How did that come about? What were your intentions ?

Brian and Kevin and I were quite happy to work together again. Basically, what we started off doing was some film music. Whether it got used for the film or not, I can't remember now - but that's how we started making the album... and we just stayed in the studio! There must have been a bit of money around at the time (laughs). The Stones put some cash up for Sahara Music. We did actually spend quite a lot of time in the studio, not necessarily doing anything productive, just buggering about....

You laid down enough material for the album. Were you pleased with the results?

Personally, it's my favourite record out of the three. It's the most contemporary - I mean it's got all the ideas there which I still use today in terms of the guitar. On those sessions, that's where I started to play the guitar properly.

Is that the one you're pictured playing inside the BB Blunder gatefold?

Yes, that's the one, the Fender Telecaster. Being left-handed I didn't have much choice when it came to guitars. A Gibson would have been nice, but I got this left-handed Telecaster, the only one in London in 1967! Giorgio bought it, I should say. The management put up the money. He thought it was a very good guitar to get because Steve Cropper had one! So anyway, the first night I got it I took it home, I took it to bits, stripped all the paint off it, (this was a brand new guitar, mind), got my dad's soldering iron and carved all these designs on the front of the wood. Then I got some button polish and polished it up. I took it back to the office the next day, because we were rehearsing, and Giorgio went apeshit! I couldn't understand it, because it looked so much better than shiny yellow. I was intending to just polish the wood until I found what a crappy piece of wood it was, so I carved and decorated it. I played that guitar, or versions of it, for years. It got really hacked about. At one point I put Gibson pick-ups on it. But essentially a guitar always sounds like itself, no matter what the pick-ups because of the resonance of it, the density of the wood, the scaling, the camber of the neck - it al

ways retains its particular nuance or sound. A few years later a friend went to the States and I said, as a joke, "pick up a Gibson for me when you're in New York" - and he did! I thought it was bloody good of him. I've still got the old Telecaster, though. (At this point said guitar was duly produced for inspection.)

My god, it's looking just a bit different now!

Yeah, I've had it rebuilt. It's still the old 1966 Telecaster neck, but now I've got a guitar synthesizer built into it.

Tell us about the back cover shot on the BB Blunder album - what's the significance of the Blossom Toes album sleeve in the rubbish bag?

That was shot in 1971 when they had that

big dustmen's strike and there was rubbish everywhere. You

couldn't actually go anywhere in London to take

pictures without finding a pile of rubbish behind you - so

we thought we might as well make use of it. The

photographer turned up at the studio while we were drinking cups of

tea, so we all walked out into Kensington Church Street. I took my

tea with me and Kevin picked up a copy of "We Are Ever So Clean".

He turned round and shoved it in one of the rubbish bags.

It was completely spontaneous.

everywhere. You

couldn't actually go anywhere in London to take

pictures without finding a pile of rubbish behind you - so

we thought we might as well make use of it. The

photographer turned up at the studio while we were drinking cups of

tea, so we all walked out into Kensington Church Street. I took my

tea with me and Kevin picked up a copy of "We Are Ever So Clean".

He turned round and shoved it in one of the rubbish bags.

It was completely spontaneous.

It wasn't a heavy-handed statement or anything then?

No, a light-handed one! (Much laughter.)

Did you gig much as BB Blunder? I've heard a couple of radio shows you did.

Yeah, we did quite a lot actually, universities, stuff like that with Family and King Crimson. We were LOUD. We had all this equipment, stacks of speakers across the back of the stage. We decided that we were going to be the loudest band in the world! We were certainly the loudest band in this country - and it was horrible!!! In the end, the roadies refused to put all the gear up on stage. They said "no way - you're going to kill people!" I've got tapes of the band from that period, but it's so loud it's completely distorted, unlistenable!

For how long was BB Blunder actively endangering the nation's ears?

I can't remember, to be honest. Sahara ran out of money.

What about Reg King's involvement?

Towards the end of Blunder's existence as a band, Reg King joined us as a singer. I'd decided that in order to play the guitar the way I wanted to play it, I didn't want to be bothered with singing, particularly. Little did we know that he was just on the turn. He was about to go completely round the bend! As soon as we went out on the road, he started disappearing from gigs. He'd be found wandering round Wolverhampton, oblivious to where he was or anything.

Did Alan King play with BB Blunder for a while as well?

Bam Bam. Yeah, he did. We sort of expanded, got two guitars and a piano and Reg - and then it all folded!

A lot of these activities seemed to intermesh. You all played on Andrew

Leigh's "Magician" album, and most of Mighty Baby backed Gary Farr.

It was like a record company thing. We just ended up playing with each other. No great plot, it's just the way it was.

How did you make the transition from ear-splitting rock to playing in what was essentially a jazz group - I'm thinking of Solid Gold Cadillac?

Well, I've been working with jazz musicians over the past ten years or so, but quite honestly I've never had a great interest in traditional jazz as such - and I don't play with jazz guys when they play that sort of music. The attractive thing about playing with jazz musicians is that there is more chance to improvise; it can be more expressive. I'm not saying it necessarily is. It's very staid and traditional in lots of ways and rock music is in fact a lot more progressive than jazz is to my mind. There's much more openness within rock to new things than there is in jazz. Jazz is still very, very traditional - even at the improvised end of it people still give you funny looks if you tune up with guitar synthesizers.

They think it's a heresy!

Yeah. There's plenty of that going down, which is a shame, because the whole idea of it is to be artistic - and to be artistic you have to invent things, otherwise you're just mimicking what's already been done. The point is though that when Julie met Keith, all of a sudden there was this sort of jazz thing - plus I'd been totally mesmerised by John McLaughlin's record ("Extrapolation"), so playing jazz rather than listening to it started from meeting Keith. Then Roger Sutton, who'd been involved with Brian Auger, was playing alongside Gary Boyle in Mike Westbrook's band. When Gary left, I got a `phone call from Roger saying "do you want to come and play in the band I'm in called Solid Gold Cadillac?" I didn't even know who Mike Westbrook was at the time! I went down and played with them and I really enjoyed it, so I thought "yeah, I'll have some of that." I'd had an offer to join Procul Harum but I felt I'd had enough of rock bands for a time and I'd give it a go with the jazz nutters! All these guys could improvise at the drop of a hat and they were good, you know. Joining them seemed like a progression, and so it was, from both a musical and an artistic point of view.

What's the main difference between playing guitar in a rock band and a jazz outfit?

Well, from my point of view there isn't a lot at all - it was just an extension of what I'd already done. I'm not that interested in jazz guitar playing. I just like the idea of being able to express yourself on an instrument. It doesn't interest me personally, as a guitar player, to follow any jazz tradition. I'm not saying I don't like it - if Barney Kessell came on, or somebody like that, I'd listen and think "yeah, that's okay"; but it doesn't do anything to me. Whereas when I listen to Jeff Beck when he's playing well, that really moves me. It's just a personal thing. It

lifts the hairs up at the back of my neck! Jazz guitar playing doesn't do that for me and never has. Therefore I wouldn't class myself as somebody who went from rock guitar playing to jazz guitar playing. I'm basically a rock guitar player who plays with jazz musicians.

Is that any different from just jamming?

Well, there's more to it than that. When working with Westbrook I've always been given an awful lot of room within his music to make my own way, so that's how it's worked. Basically, I guess he likes the way I play or interpret his music (or he wouldn't keep calling me up). I don't see any big transition from rock to jazz - just an extension of what I've always done. The same is actually true of improvised music. I find playing with certain musicians in an improvised way is a further extension of the whole thing. All you're doing really is you're making sounds and you're co-ordinating them to try and have an effect on the people you're playing with or the people who are listening. I play for pleasure now - in as much as if I don't enjoy it, I'm not going to do it.

After working on Keith Tippett's Centipede project, you recorded with Mike Westbrook on "Citadel Room 314" and then as Solid Gold Cadillac.

Yeah. We cut "Brain Damage". That's a great record. It's really quirky stuff, you know. Some of it sounds like really duff pop!

Then there were contributions to Julie Driscoll's "Sunset Glow" album and to

some Magma sessions.

The Magma thing was Giorgio again. He called me up and said "You must come to France." He managed Magma, they needed a guitar player, so I went over and ended up staying a couple of months to play on the record but I never joined the band. Christian Vauder was their drummer and front-man. They wanted me to join, but it didn't happen. They were a pretty heavy-duty group. I would have liked to work with them on a permanent basis, but they were in France and I didn't seem to have the time to commute.

And Mirage? You lent your services to the recording of "Now You See It" in 1977.

Mirage was an English outfit with George Khan on saxes and Dave Sheen on drums. That was where I first worked with Dave. Some good times.

Then you spent quite a lot of time working with Kevin Coyne and recorded "Bursting Bubbles", "Pointing The Finger" and "Sanity Stomp".

Yeah, we made a few records together, co-wrote a few tunes. I really enjoyed that. It was a completely drunk, loony time.

I understand Kevin spends most of his time in Germany these days. Could you happily live and work on the continent?

Well, there's not so much freedom anywhere as there was ten years ago and there's chaos in Europe at the moment. I toured Yugoslavia with Eric Burdon a couple of years back and we had no idea that this could happen. It's unbeliev

able. I can't comprehend it. I've been to a lot of those places and I just can't correlate the two things.

If you're not playing a lot at the moment, are you writing new things?

Well, I've never written. I compose. Writing is another process. What I do is more like painting. I do it all the time. I'm always fiddling round with ideas, which is how I work anyway. But from a performing point of view, at the moment I'm involved in improvising. Right now I'm working with a trumpet player and that's all improvisation, but I would consider it to be composition as well. If you do it with the right attitude then you're composing instantaneously, which I think is really enjoyable. In Europe, improvised music stands for something other than just music. It's got political undertones. How people play and who they play with represents some sort of political stance. It's got heavy-duty connotations which I personally don't enjoy. To me, music or art are there to try and transcend all that bullshit - not to get bogged down in it.

I notice you're using a synthesizer...

I think they're useful and becoming more and more useful. They're becoming a creative tool now.

I don't have a lot of time for sampling.

Sampling, yeah. It's a pain in the arse. But having said that, if you can get some decent samples you can use the sound and start mucking around with that sound, take it from basics to work with. Pop music itself is based on a few chord sequences and bar lengths and keys. Most rock and roll is in E or A - like the complete works of AC/DC is in the key of A! They use other chords, but they're all in the same key. Whereas folk music uses C, G and D. You don't get a lot of Cs in rock and roll, not as tonics. You get a lot of jazz in B flat, especially stuff like saxophones, because that's where they're most happy playing. That's why they hate playing with rock and roll guitar players (laughs).

How did the deal for "Slaughter On Shaftesbury Avenue" come about?

It's just a lot of stuff that got recorded. GLS was an offshoot from Mirage. When Mirage went its sweet way, Dave Sheen and I still wanted to work together. We needed a bass player and Dave had met Steve Lamb up in the Lake District. So we checked him out, discovered he was a fantastic bass player, and that's how GLS was formed. A lot of the life of GLS was in fact working with Kevin Coyne. That wasn't intentional, but it was OK. The GLS stuff on "Shaftesbury Avenue" is from an album we recorded at Alvic Studios. I'd like to get the rest of the GLS tapes released one day. Then there's Other Routes. That has Dave Barry who I used to work with along with Mike Westbrook. He liked GLS, so he put together Other Routes which is him, me plus Steve and we did some recording. So there were all these tapes accumulating and not being used over a period of time. John Platt suggested I get in touch with Reckless Records who were looking to put out some albums of British guitar music. So I

sent off tapes of GLS, Other Routes and Full Monte and they said "Why don't we put a record together using bits of it all, seeing that it spans such an amount of time, rather than just putting out a GLS record that is 7 years old." So I said okay, and that's what the record is, a compilation of things that I was involved in over that period. But, you know, there are guys who are a million times better guitar players than me who have had extremely hard times - like Allan Holdsworth. He had to go to America to be taken seriously. There's nobody around in this country (promoters especially) who has any taste! It's all hit and miss. Take somebody like Keith Tippett. He's not exactly having an easy time. He's doing this, that and the other, but there's times when he's not doing anything at all. There's no continuity to anything over here. Mike Westbrook has got an OBE for his contribution to British Jazz Music, yet can he get a fucking gig for his own big band? No chance! And if the bands don't get the work, people just drift off, like Other Routes.

Bring back Giorgio Gomelsky!

God, yeah. That's the trouble, you see. There are no Giorgio's around. Whatever you say about Giorgio, he was a man who was interested and he put himself into it. He was the only person who was interested in the creative side of it all.

Finally, can you let us have an update on your activities with Full Monte?

We gig occasionally, round London and at clubs and festivals.

We're also doing a mini-tour at the end of this year [1993]. We've done some DAT recording and produced a cassette which we sell at gigs. That tape was actually the first time we played together. We decided that rather than go to a rehearsal we would go down to Tony's recording studio and have a play, which is what we did. It's a kind of getting-to-know-you tape. I'd never played with Marcio Mattos until we started recording that stuff. It's just totally improvised. We just plugged in and said "Go!"

Postscript - the mini-tour did happen (funded by the Arts Council) and took Full Monte to Sheffield, Leeds, London, Swindon and Exeter at the tail end of 1993. The gigs were recorded for a possible live release in 1994.

Written and directed by Steve Rowland, produced by Phil McMullen (c) Ptolemaic Terrascope.