You’ve undertaken a massive project, trying to encapsulate the history of psychedelic / acid folk into a single book. Where did the idea originate?

I felt that nothing really satisfyingly comprehensive had been written on the sound, especially nothing that took a long view of it. There were some individual magazine articles and blogs, but nothing much bigger. As a fan of the music, I thought I could tell the story, and I really wanted to! Also, on a more conceptual level it was interesting to me to explore why the sound came back into vogue for younger people after so long being pretty much dismissed as unfashionable hippie tedium. I went into the book as a curious fan, not a font of existing knowledge, and I hope that helped the style of the book.

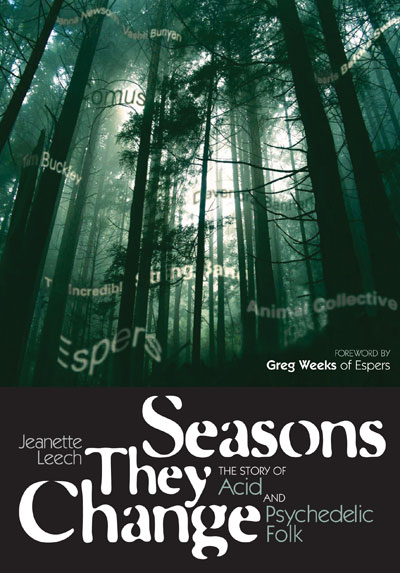

You began the book under a different title. What prompted the change (no pun intended!)

My original title was Shifting Sands, a reference to two songs that I liked a great deal – one by Synanthesia and one by Rusalnaia. The title represented what I thought of as the changing fortunes of the genre itself. After a chat with the publisher, who was concerned that the Shifting Sands references were too obscure, I was asked to consider some alternatives. I came up with Seasons They Change – a better-known song to genre fans and more casual observers – that also kept the spirit of shifting fortunes and the passage of time.

You’ve chosen to present the book as an historical narrative rather than your typical compendium format, alphabetically listing all your entries with brief career synopses and key releases. Explain your approach and why you thought the narrative approach would work better.

There are plenty of excellent books that do that, such as Galactic Ramble, but I never ever wanted to do it with Seasons. One of the things I was really keen on was making connections between the past and present. On an obvious level, there’s collaborations, but there were also more nebulous things like shared sensibility, difficulties with labels and releasing, approaches to art itself… they wouldn’t have been easy to bring out in a compendium format. It was probably making more work for myself but it’s how I wanted to do it!

The field has become so large over the years, with many acts retroactively tagged as “acid” folk, how did you ever decide where to draw the line? Some acts seem to just get a name check, whereas others get a few paragraphs or pages.

It’s a line in the sand – couldn’t ever be anything else. To an extent the book reflects those artists whose experiences or music I found particularly interesting, but I tried to be aware of it and contain it in a more objective narrative. There were certain people who, through their popularity or influence - Incredible String Band, Devendra Banhart, Vashti Bunyan, Current 93 all spring instantly to mind – who would necessarily have a larger role to play in the story. Then there were people whose role changed in my planning as I was doing the interviews. Tim Buckley is a good example here. I hadn’t really considered him as having a major role at the outset, because his music is not overtly psychedelic, but as I was talking to people it became clear just how important his overall experimental approach to folk music was. And how, in particular, he influenced many of the newer free-folk generation.

I noticed you’ve avoided your own definition for your subject matter, yielding to Lillian Roxon’s use of the term in her Pearls Before Swine entry. Was that intentional on your part – not to define the term so as to potentially paint yourself into a corner?

Well spotted! I hate genre terms being used as a tie. To me, it’s much more interesting to note the etymology of the words and how they are applied over the years. Actually, I think Roxon’s reasoning for her term – that the music comes from the same exploratory impulse that led people to take LSD, rather than being music made under the influence of LSD per se – is excellent. Perry Leopold used the term in a very specific way to relate to LSD but Sonja Kristina (on her 1991 ‘Songs From The Acid Folk’ album) didn’t. I like the way it was taken by different artists and used in complementary ways.

Having said that, how did you decide who to include and who to omit?

Partly it was the very practical considerations of word limit and space. When I did have to make difficult decisions, I tried to cut down on things that had been well-covered elsewhere, like the Marc Bolan story. But, inevitably there will be disagreement on who should have been granted more or less space, or who I should have put in… part of the fun for the reader! I do it mysel f with music books, so can’t really complain when others do it to mine! f with music books, so can’t really complain when others do it to mine!

There’re literally hundreds of artists and seemingly thousands of recordings mentioned or discussed at some length in your book. Did you ever count how many artists and records are actually in there?

No. I think I went mad enough writing the book as it was.

And you must have one helluva record collection if you actually own all the records you discuss. Was it difficult tracking everything down (some are quite rare) or did you rely on external references for some of your information?

Yeah – I don’t have all of them, nor could I afford to get all of them! This was my route to finding records. 1. Do I have it in the house? 2. Is it on Spotify? 3. Does a friend or contact have it so I can borrow it? 4. Can I buy it? 5. Is it on the internet? With these I got everything, and was able to keep the costs as low as I could, also while trying not to illegally download. All the records I discuss I’ve heard; I would never rely on someone else’s opinion for describing a sound.

While you reference key releases from each of the artists, you’ve elected not to include an “Appendix of Recommended Listening” for newcomers to use as a shopping list to hunt down essential recordings. Was this a conscious decision due to space limitations or something imposed by your publisher?

In my original vision, I thought about doing this. But it soon became clear that, yes, space would be at a premium. I also didn’t really like the idea of a comprehensive “list”. I did however do a couple of Spotify playlists. One is a mammoth 15 hour marathon that includes songs from each chapter (Seasons They Change), and the other is a 20 track primer combining some personal faves and bigger names (Seasons They Change: A Primer). [Note: The Spotify service is not available in all countries.]

Along those same lines, it seems that a book such as this cries out for a cover CD to introduce people to the numerous obscure artists you discuss. Was it an economic decision not to include any music with the book? Was that something you ever considered?

To an extent the Spotify lists – although I know not everyone has Spotify – could provide a bit of an introduction. But it was never something on the cards and I think it would have been a very time consuming exercise for both myself and for the publishers.

Did you actually relisten to all the records you mention to refamiliarise yourself with the material or were you in some cases evaluating from memory?

Yeah, I did relisten to everything. No wonder I stopped listening to acid folk for a few months after submitting the manuscript!

You interviewed our illustrious editor, Phil McMullen, and over two dozen artists who’ve performed at the various Terrastock festivals (i.e., The Terrastock Nation) are included in your book. How important would you say the Ptolemaic Terrascope and its online successor have been to the acid folk movement?

Very important! Phil was amazing, right from the first time we made contact. If anyone had the right to write a book on the genre it was him, so I was super-nervous about making contact and explaining myself. Yet he was never anything but supportive and helpful. Our first ‘interview’ turned into a drinking session and the Dictaphone never even got switched on! The Terrascope was very important for that feeling I mentioned earlier, about wanting to link up the past and present – the magazine and the festivals were both very keen on doing that. Also, as I write in the book, a lot of artists who would go on to make fantastic records in the 2000s were avid readers of the magazine in the 1990s. Terrascope’s coverage of people like Tom Rapp was crucial for such artists becoming an influence on a new generation.

I have to ask abou t the book’s jacket photo. I’m sure I’m not the first person to ask why you’ve placed Joanna Newsom’s photo in the spot usually reserved for the book’s author. Do people who’ve failed to read the back jacket still think that’s you?!! What was the thought behind the unintentional subterfuge? t the book’s jacket photo. I’m sure I’m not the first person to ask why you’ve placed Joanna Newsom’s photo in the spot usually reserved for the book’s author. Do people who’ve failed to read the back jacket still think that’s you?!! What was the thought behind the unintentional subterfuge?

Ha! Yeah, there was palpable disappointment from friends that Joanna beat me to the back cover! I think it was just a house publishing decision, to be honest. Either that or they think I’ve definitely got a face for radio!

So what is the future for psychedelic acid folk? Are there any artists to watch out for since your book was published?

I think, certainly commercially and to a certain extent creatively, the sound has peaked once again. That’s fine; I think it’s a natural cycle. But there are still wonderful records out there. For me personally the most mind-blowing stuff is coming out of Finland and Fonal Records. I’m constantly impressed by the Rusted Rail label in Ireland and loved the recent CUBS album they put out. The Temple of LIB album from last year was really special, too.

Our heartfelt thanks go out to Jeanette for taking time out to satisfy our curiosity about how her marvellous book took shape. She welcomes your comments or requests for more information about her book.

Link to Jeff Penczak's review

Interview: Jeff Penczak. Introduction: Phil McMullen. Huge thanks to Jeanette for making dreams come true. |