My introduction to Powell St. John came in the early 1980's when I started buying 13th Floor Elevator albums and saw that several of the songs were written by "John St. Powell." I later found out that the Elevators label, International Artists, had intentionally re-arranged his name in an attempt to not pay him royalties. In the decades that followed, the name Powell St. John continued to be a mystery of mystical proportions. Besides writing the lyrics to Kingdom of Heaven, You Don't Know and Monkey Island for the first 13th Floor Elevators album "The Psychedelic Sounds of" he wrote the lyrics to Slide Machine on the "Easter Everywhere" album, and You Gotta Take That Girl on the "Live" album. He also wrote the lyrics to Bye, Bye Baby for Janis Joplin and I Will Forever Sing The Blues for Boz Scaggs, he was a founding member of the Conqueroo and an original member of sixties California band Mother Earth, and played and wrote lyrics for their first two albums. In 2005 Powell was inducted into the Texas Music Hall of Fame and he then went back into the studio in Austin Texas and recorded the two disc CD "Right Track Now" that includes former 13th Floor Elevator members Roky Erickson, Ronnie Leatherman and John Ike Walton. He also started playing out live again backed by Roky Erickson's former band the Aliens and their has been talk of future shows and recordings with the legendary Austin Texas band Cold Sun and their founder Billy Miller. It's comforting that some 60's icons never sold out or compromised what they know to be true. On to the interview....

Where did you grow up and how did you get started in writing and music?

I was born in Houston, Texas on September 18 1940. In 1943 my dad quit his teaching job at Pershing Junior High and moved the family from Houston to a truck farm ten miles down river from Laredo, Texas on the boarder with Mexico.

For the next five years I ran wild in the desert, the only kid on the farm most of the time. It was a great growing up experience.

In 1948 my dad went back to teaching and two years later we moved in to Laredo proper. I graduated high school there in 1959.

Music was not a big thing to me during my formative years. I discovered harmonicas when I was about twelve and learned to play a little but it was only for my own amusement and I had no thoughts of pursuing music as a career or anything of the kind.

Once I was a student at the University of Texas at Austin my world opened up. I thrived in the academic environment and soon met kindred spirits and began to experience a wealth of new ideas and experiences. This was the time of the Folk Revival and homemade music was everywhere. Everyone had a guitar. As luck would have it one of my room mates had a little brother who was an accomplished guitarist and banjo player and he encouraged me to play along with him on my harmonica. I did and it was great. It was quite a revelation to a lad who had long ago despaired of ever getting a symphony orchestra to back him up like John Sebastian Sr. or Larry Adler had.

The guitarist/banjoist was a guy named Lanny Wiggins, and he and I formed a duo we called the Waller Creek Boys. In the summer of 1962 we added another Waller Creek Boy, this one named Janis Joplin. After that music became a big thing, maybe the biggest thing in my life.

As for song writing, I suppose the example of Bob Dylan's writing had a lot to do with that. He gave me permission, so to speak, to compose my own songs when the traditional material did not quite carry the message I wanted to convey. Remember too, the Vietnam War was heating up and songs of social protest were being generated apace. This too was validation of my desire to write my own music. So I did.

![]() How

long were the Waller Creek Boys a band? Did you do any recording and what

kind of places did you play?

How

long were the Waller Creek Boys a band? Did you do any recording and what

kind of places did you play?

I suppose one could say we were playing together from sometime in the summer of 1962 through 1963, maybe into 64. The association was rather informal anyway so it is hard to say exactly when it began or when it ended.

Lanny Wiggins and I had been playing together since the previous school year but the enterprise expanded enormously once Janis hit the scene, and things cooled down considerably for the WCB after Janis departed on her second, trip to the west coast, the bum trip.

By then however, Lanny and I were involved with other interests and with less time to devote to hanging out and playing, we were drawn in different directions. Besides, by then I had begun to work now and then with Kenneth Threadgill and different avenues for expression were opening up for me.

As far as recordings by the Waller Creek Boys there are a few. Remember that in those days recording devices were just being introduced as consumer electronic products. My friend Jack Jackson had the first one I ever saw. Jack recorded a number of tapes of the WCB, Janis, and everything else. Soon after I saw Jack's machine I had to have one of my own. I recorded the same things as Jack. It was a real novelty. The WCB never saw the inside of a professional recording studio however, so those "garage tapes" are all there are.

I have been trying to remember the places we played in those days. The folk revival was sweeping the country and we played a lot of places because that was the kind of music we played and it was popular. I don't think we were ever paid or even offered any pay. Beer, yes pay, no. Our venues were basically any place where they didn't run us off, parties, the University folk sing, the back yard of the Ghetto, etc. and most significantly, Threadgill's Tavern.

How did you get to know Janis and what was your impression of her?

I mentioned earlier about the accelerating effect the arrival of Janis Joplin had on the musical fortunes of the WCB. Janis had just returned from her first trip to San Francisco where she had been hanging out on Grant St. with the last of the Beat Generation. She said they called her their "little jive chick from Texas".

I was an art student with a subscription to the Village Voice, a guy who read everything he could find about bohemian culture and the hip scenes so far away. So the arrival of Janis brought me someone who had actually been to one of these hip places and could teach me the language and maybe make me hip too. Then I heard her sing!

Needless to say I was smitten. Here was a cool chick, savvy to the ways of the world outside my limited frame of reference, who was also a dynamite vocalist and folk musician with a knowledge of the genre far greater than mine and probably Lanny's combined. Besides, at 19 Janis was pretty hot. She had to become one of the Boys.

Was Janis outrageous and loud when you hung out with her and at Waller Creek Boys shows?

Janis was the sort of person that could call attention to herself just by entering a room. Yes she was loud, sometimes obnoxious, and definitely outrageous, especially to those we referred to as "squares" and "straight" people, and that was not just at shows, rather it was all the time.

Have the recordings with Janis ever been released?

As for the home made tapes I mentioned, there has been at least one abortive attempt to release some of the material commercially. As I understand it the effort failed due to conflicting claims of ownership which caused the label involved to abandon the project. To my knowledge no other official releases have been attempted. I would like to change that and am working to do so however there are many pit falls and navigating them is a real challenge.

Yeah, It would be great to see that stuff get released. It's amazing that there is still unreleased Janis Joplin music! So how did you meet Tommy Hall and the 13th Floor Elevators?

How did I meet Tommy Hall? At this point I have no recollection of actually meeting Tommy for the first time. It would have occurred sometime around 1962 or 63. Tommy attended our parties and gatherings. In those days he was somewhat more conventional than he became in later years and maybe that is why I don't remember our initial encounter. Tommy was a jug player even way back then and, since no one else played that instrument he found a place in our impromptu musical sessions. He and I became friends because of our mutual interest in music. We were big Bob Dylan fans as well. One thing we never did was talk politics.

By the time Tommy set out to form a band to push his ideas he and I had been friends for quite a while. The band he formed rehearsed in a secret location and I met them like everyone else did when they were unveiled at their debut concert. Actually I had met Roky sometime before this when Tommy and his wife Clementine took me to the Jade Room to see Roky perform with his band The Spades. Tommy allowed as to how he was going to woo this kid away from The Spades and put him with some guys he knew from Port Aransas down on the coast. He did and that was the genesis of The 13th Floor Elevators.

And how did St. John and the Conqueroo Root get started?

As for the Conqueroo, the Band was first called "St. John and The Conqueroo". After I left town for California in 1966 the band became just "The Conqueroo". There never was any "root" on the end of it. We formed in response to the times in late 65 or early 66, I forget the exact date. The Brits had invaded the American music scene in a big way, The Elevators were playing gigs, Bob Dylan had turned electric and was not looking back, and it seemed to us that we could get in on that action too.

I remember on August first 1966 the Conqueroo had been rehearsing at a place out on the lake and I had left early to go over to the east side to get tickets for a James Brown concert that was to take place that night. On the way I turned on the radio to hear that there was something happening on the UT campus. Some guy was up on the tower shooting at people! The cops were understandingly in an uproar and students and citizens of Austin were advancing on the tower, deer rifles at the ready. Little did I know at the time, as I was driving down Martin Luther King, (then called 19th street), that I was within range of this former Eagle Scout and Marine sharpshooter.

When I got to the ticket outlet, I don't

recall the name of the place, it was filled with black folks listening to

the radio account of the happenings on campus and looking anxious. When I

entered they looked at me and I looked at them and we each knew what was on

the other s

mind. They were thinking, "Dear Lord don't let this guy be black." I was

thinking, "Dear Lord don't let this guy have long hair." We each knew

that if our fears were true that our communities would suffer as never

before. We were saved when it turned out that the guy was white and had a

crew cut. Whew!

s

mind. They were thinking, "Dear Lord don't let this guy be black." I was

thinking, "Dear Lord don't let this guy have long hair." We each knew

that if our fears were true that our communities would suffer as never

before. We were saved when it turned out that the guy was white and had a

crew cut. Whew!

About three weeks later I left Austin for Mexico, vowing never to return.

Can you talk about what instruments you played in the Conqueroo, and how did you become such a great harmonica player?

In The Conqueroo I played harmonica mainly. I did play amplified kazoo on Land of a Thousand Dances but basically I was a harmonica player and occassionally, the singer.

As for being a "great harmonica player", thanks for the compliment. I don't know about "great" but I think I'm pretty good. I got into playing harmonica after I was forced to abandon my original goal of becoming a flautist. As a child I suffered from raging ear infections. These were not the kind of affliction that causes babies to be cranky. These were the kind that causes the victim to writhe on the floor screaming in agony. Anyway, the doctors thought that playing the flute caused infections in my throat to be blasted up into my ears. So it was determined that I was to drop the flute. Bummer!

What was your vision for this band, any memorable shows, and are there any unreleased Conqueroo recordings?

Well there must have been something in my psyche that had a need to play music because after losing the flute I then endured a year of lessons in rudimental drumming. Learning rudimental drumming would allow me to march in the band with a trap drum strapped to my body. I hated rudimental drumming and I was not enthusiastic about marching in the band lugging a trap drum. I gave up rudimental drumming on my own.

Sometime during all this, I'm not sure when exactly, I was cruising the dime store, probably on a Saturday since that was the day I usually took the bus into town and went to the Saturday matinee at the picture show. After the movies I would hit the dime stores looking for anything interesting so as to blow my allowance. On this particular day I found a harmonica. It was a small diatonic job, probably a Marine Band model made by the Hohner company. In those days one of those sold for under a dollar.

(Today they list at $30.00 by the way). Riding home on the bus I sat way in the back and tried to see if I could play anything. Lo and behold, by the time I reached my stop I was playing a Steven Foster song. It was the old, very politically incorrect song Foster wrote about the passing of an old and beloved slave, Uncle Ned. The chorus goes:

"Lay down the shovel and the hoe

Hang up the fiddle and the bow,

They'll be no more work for

Poor old Ned,

He's gone where the good

Darkies go."

That experience got me going. I no longer felt the necessity to be in the band. I had my ax. The only thing was, I never heard any blues harmonica so I knew nothing about that, and, in fact, the only harmonica I heard on the radio was John Sebastian senior playing classical music or maybe the Harmonicats doing Peg O’ My heart. At eleven or twelve years old I could see no way that I could enlist the services of a symphony orchestra so I couldn't do classical music and I didn't know any other harmonica players so anything like the Harmonicats was out as well. What to do? I kept playing, just for me and just for fun. It was that way through the rest of my formative years. It was only after I came to Austin and met Lanny Wiggins that I realized that I might be able to play in an ensemble after all. Then I really began to concentrate on learning all I could about playing the instrument.

You asked what was my vision for the Conqueroo. I remember having visions occasionally in those days but I don't recall having one specifically for and about the Conqueroo. If there was a vision I guess it would have been to get out there and get some attention like the Elevators were getting.

I don't remember many of the shows we did. We did play a club called "The Fred" which was frequented by the usual rowdy bunch of good old boys. There were fist fights almost every night and belligerent drunks were the norm. My friend Steve Porterfield would come down to the place when we were playing and set up his "Jomo Disaster Light Show" to accompany our set. This was how we found out that a strobe light could bamboozle a drunken red neck to the point that he couldn't throw an effective punch and sometimes would even nauseate him to the point of regurgitating his beer. Too bad we didn't get anything on film, these were the days before video cameras.

While I was with the band we were not recording as The Conqueroo. Ed Guinn, Bob Brown, Walli of Austin, Minor Wilson and I (I hope I haven't left anyone out), went down to Houston one weekend and spent the entire time recording with Frank Davis as the engineer and Bob Simmons as the producer. None of us had ever recorded before and the results were somewhat short of spectacular but it was all experimental anyway and a good introduction to marathon recording sessions. I don't know if any of this has survived.

After I departed Austin in 1966 the Conqueroo made several recordings which were released commercially.

How did you come to write for the 13th Floor Elevators?

I was a personal friend of Tommy Hall and his wife Clementine. I suppose I had known them for two or three years prior to the formation of the Elevators. We shared tastes in music and the written word. Tommy was a big fan of Bob Dylan and so was I. I used to go over to their house to visit and chat. I enjoyed their wit and sophistication. Tommy made me aware of a lot of things.

Where did the insight come from?

Being a friend of the Halls, I was around when Tommy got the initial conception of what came to be the Elevators. This was Tommy's insight. He told me he wanted to use the power and drama of rock n roll music to spread the message of altered consciousness and higher mind. He knew that I had been reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead, (Tommy may have loaned me a copy, I'm not sure), and he knew also that I myself had been experimenting with mind expanding substances, so I guess he figured my head was in the right place. At the time I was drawing inspiration from those mind/spirit expanding experiences and my songwriting reflected this. Tommy listened to my material and chose several tunes right away.

What was your impression of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators?

Once the skepticism of Austin's hip community was swept away by the Elevator's debut concert at the Jade Room, and it was accepted that we had a first rate rock n roll band in town, the Elevators became one of Austin's hip icons.

I was able to get to see these guys on a regular basis, sometimes even attending rehearsals. The rehearsals were an eye opener for me because in those days I naively believed that a band made up of "experienced" individuals would not have disagreements and would not behave like ordinary human beings. Everything would take place on a higher level I believed. Well they did behave like ordinary human beings and they did have disagreements. John Ike and Roky mixed it up quite a bit. That revelation led me to begin considering the band members individually rather than as some sort of nebulous superbeing. What I saw was a group of highly skilled musicians working as a unit. John Ike, Benny and Stacy formed the basic unit. They were already a seasoned band, used to one another. Added to this was Roky, the phenom vocalist and Tommy the jug virtuoso and constant looming presence.

What was the artistic statement?

The Elevators' artistic statement was a fusion of the musical minds of guitar genius Stacy Sutherland and Roky Erickson and the haunting lyrics of Tommy and Clementine Hall. The statement which resulted from this musical stew consisted of rock solid rhythm and blues, and rock and roll, performed flawlessly and with tremendous energy. Atop this was Roky's singing, wailing out the vocals, delivering the message loud and clear. The result was stunning.

What was the public reaction?

The public reaction to the Thirteenth Floor Elevators depended on which "public" you meant. Remember this was 1965 and the youth culture had already found a number of reasons to be at odds with the dominant paradigm. Among those of us who were on the youth culture side, especially those with pretensions to hipness, all reacted favorably. The Elevators played good music and they were exciting. How many young folks actually received the "message" I do not know but I know many of them did.

The reaction of the rest of society was totally predictable and has been well documented. The Elevators scared the hell out of them.

Benny Thurman, original bassist for the Elevators, recently passed away. Could you share some of your memories of him?

Benny and Roky were the local boys in the Elevators. I remember that when the authorities descended on Tommy and Clementine's home to arrest them for being a pernicious influence, Benny was the only member of the band that was not apprehended. Somehow he managed to be somewhere else that day.

I remember that when he played he had a habit of whooping from time to time. I believe he can be heard doing that on the Elevators' cut of You're Gonna Miss Me. I always liked his playing. Benny was a good old boy.

The Paul Drummond book, "The Saga of Roky Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators, the Pioneers of Psychedelic Sound," has a lot of emphasis on Stacy Sutherland and really made me rethink his role in the band, him as a 60's rock "outlaw" and just him as a person. Could you talk a little about how you saw Stacy?

It is my opinion that Stacy's guitar work was fundamental in shaping the sound of the band. On stage he had a smoldering presence, like a burning gasoline tanker just before it erupts into a full fledged conflagration. It was that energy and drove the band.

Do you play any of the harmonica on the 13th Floor Elevator recordings? Did you ever play with them live or in recordings?

I never recorded with the Elevators. I sat in with them only once. I don't recall the venue.

How did your involvement with the band Mother Earth come about?

In the December of 1966 I arrived in San Francisco with the vague idea of finding work as a harmonica player or some such in the vibrant music scene that was flourishing at that time. Nothing presented itself immediately however and the spring found me still scratching my head as to how to proceed. At this point enter Travis Rivers. Travis is an old friend, a member of the Austin scene and one of the many Texas expatriates, (The Texas Mafia) that had settled in San Francisco at that time. Travis was the editor of the Haight Street Oracle, a street sheet type of community newspaper created to allow the throngs of homeless kids something to offer for sale when bumming spare change so they could not be rousted for panhandling. The paper was free to anyone who came to the paper's offices and asked for some to sell.

Due to his position as the paper's editor, Travis knew a lot about what was going on in the community. Knowing that I was in town and looking to get into music, Travis introduced me to Ira Kamen, a Chicago guy who played a Hammond B3 organ. Ira had the same idea about getting into the music scene as I did, and he knew chick singer from Madison Wisconsin named Tracy Nelson who was also looking to get into music in SF. Ira and I travelled to Berkeley and met Tracy. We hit it off and the three of us decided to see if we could form a band of our own. All we needed was a rhythm section and a lead guitarist. We found a guitarist, eighteen year old Herbie Thomas straight out of college in Ohio where he had been known by the nickname "Five Pack Thomas" in reference to a small retail operation he had going there. Herbie was a hot shot guitarist. I heard he went on to work with the Funkadelics.

So now we were four but still lacking a rhythm section. Once again Travis came to our rescue. Through mechanisms unknown to me Travis managed to lure the entire rhythm section, bass, drums and keyboards away from the Sir Douglas Quintet, and put them with the four of us. This is the way Mother Earth was born. Ira came up with the name and Travis became the manager.

How was it living in San Francisco at that time and what are some of your memories of playing out with Mother Earth?

Playing with Mother Earth was the fulfilment of a dream for me. With a Hammond organ on one side of the stage, a piano on the other, guitar, bass and drums in between, and two vocalists up front the power was exhilarating. One thing that helped us greatly was the fact that the rhythm section, George Rains on drums, Jance Garfat on bass, and Wayne Talbert on keyboards, was used to playing together and could fill in as a jazz trio when Tracy and I ran short of material. This was a boon in the early days before we had a long set list. There is a set featured on the website Wolfgang's Vault, recorded at the Fillmore which features this first iteration of Mother Earth. So far as I know it is the only recording made of this early band. The personnel had changed somewhat by the time the first album was cut.

Looking back on it from many years of experience I now see our success as nothing short of miraculous. In the early days we played a lot of benefits and appearances in the park to build our fan base, and rapidly, (it didn't seem so at the time), we became a fixture on the scene. The scene, you see, was very receptive. Thousands of young people were coming to San Francisco to get in on it, and since music was a dominant force in youth culture at the time, Mother Earth was in the perfect position to succeed. Within a year or so we were signed by Mercury Records and went into the studio to cut our first LP.

It seems that your role in the band changed quite a bit between the first and second album, can you talk about that?

The first LP, titled "Living With the Animals" was cut in San Francisco during the summer of 1968. In fact, while my compatriots were battling the police at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, I was in a tiny studio in a basement under the confluence of Kearny St and Columbus Avenue doing overdubs for the album.

Once the album was finished and released Mother Earth went on tour. New Years eve 1968 found us opening for the Chambers Brothers at Fillmore East in New York. The tour took us to a number of venues across the northeastern US, Boston, Detroit, Philadelphia, Lexington, Minneapolis etc. Touring was all I had been told it would be; great excitement in small doses and large doses of boredom and loneliness. Besides this it was winter and I really dislike cold weather. So, all in all touring was not a greatly rewarding experience for me. The tour ended in Nashville where we were to cut another LP.

Being in Nashville had its charms. I strolled around town whenever I could, sightseeing etc.. Still, I was homesick and Nashville was not home to me. I visited the Rhyman Auditorium and the fact that the building was abandoned and crumbling because the Grand Ole’ Opry had moved out to some soulless location outside of town just contributed to my dismal mood. It seemed that everywhere I turned some sad and forlorn scene forced itself upon my consciousness. During this time I decided to resign from the band. I wanted to get back home to the West Coast. This decision was reinforced when it was announced that Tracy, by now the headliner of the band, planned to buy the farm in Mount Juliet where band had been staying, and move the operation to Nashville permanently.

The second album was not as successful as the first one had been. For my part I believe that given my mindset coming off the tour, and with the negative experiences fresh in my awareness I was not in the proper mood for making an album. Also knowing that we would be going our separate ways when the project was finished cast a pall over the endeavour for everyone. For whatever reason, the LP seemed to lack something that was present in the first one and even the best engineers at Bradley's Barn could not provide it.

It seems that when the Elevators went to California in 1966 it was a turning point that they never quite recovered from. Were you there during this time and why do you think the San Francisco audiences didn't really embrace them?

Good question. Unfortunately I am as puzzled by this as you. Jack Jackson, (Jaxon), once speculated that a band so accomplished and professional coming out of Texas of all places, and dressed like Texans just baffled the SF audiences. The message was so raw and bold and delivered with such a stunning impact that the audiences went away in confusion.

For my part, though I was in The City at the time I was preoccupied with my own career and, in fact, never saw the Elevators perform in San Francisco. Roky came by the place I was staying once and picked up the words and music to Slide Machine. Beyond that we had no contact.

I heard the band had a difficult time on the west coast. Their equipment was stolen at one point I believe. There were probably other difficulties as well. But I think that, even with hard times, they might have caught on if they had stayed in California longer. My understanding is that International Artists compelled them to return to Houston, ostensibly to cut another record. I could speculate that IA wanted them back in Texas not only to record but because they were concerned that their dynamite act might be lured away by some other record label, but that is only speculation. Maybe someday I will be fortunate enough to get Tommy Hall to talk about it. This could happen but it is not likely. Tommy has moved on and no longer wants to discuss his illustrious rock n roll past.

I see Tommy from time to time, and these days, when one can steer him away from politics, he talks about his work which now seems to involve a great deal of mathematics. I have never been clear as to what it is that Tommy is doing. Now that his explanations are couched in mathematical terms they are more opaque than ever as far as I am concerned. As to when and if his production will ever see the light of day, I asked him awhile back if he thought I should drop acid again since I was back into music, and his response was, "Why don't you wait, my work will be done soon, then you can use it."

Go figure.

Can

you talk about what you've done musically since you left Mother Earth?

Can

you talk about what you've done musically since you left Mother Earth?

After Mother Earth recorded it's second album at Bradley's Barn outside Nashville I decided to resign and return to California. I was tired and disillusioned with the music scene, having come off a tour of the northeast in winter time. Add to that the fact that the band had decided to relocate to Nashville. I had no desire to live in Tennessee. Not to take anything away from the Volunteer State, but I was homesick for the West Coast.

So I returned to Berkeley and signed on to the unemployment rolls as an out of work band leader. Times were lean but during this stretch I became involved with the elder daughter of Tom Donahue the famous radio pioneer/promoter, band manager etc. Tom was quite a guy. His daughter, Kathleen, (commonly known as "Buzzy") is still a dear friend to me today. We made several attempts to put together working bands but to no avail.

About this time Tom dreamed up a tour. It was to be called "The Medicine Ball Caravan" and the plan was to lease a bunch of Winnebagos, fill them with counter culture types from San Francisco, including the band he was currently managing, Stoneground. The band would be booked into venues across the country and the Winnebagos full of "freaks" would caravan along. The lead vehicle was to display a large banner across the front reading, "The Medicine Ball Caravan We have come for your daughters!" Everyone taking part in the tour was to receive a round trip ticket to London where the tour was to end. The participants could then go wherever they wanted secure in the knowledge that they would be able to return to the US whenever they desired to do so.

I must say, to a permanently paranoid person like me, this seemed to be a wild and dangerous venture. I had misgivings from the start. It was not only my paranoia but also the fact that although Tom assured me that I would be playing harmonica with Stoneground, I couldn't help but notice that no one from the band had invited me to do this and there was no indication that they needed or wanted a harmonica player. I worried that I would wind up being a fifth wheel, just there because I was tight with the promoter's daughter.

In the final days of preparation for the tour my ongoing job search bore fruit and I landed a position with a small mom and pop jewellery manufacturing operation in Oakland. I took the job I think, because I never really intended to go on the tour with this bunch of crazies, and besides that, having the job gave me a chance at a future on the West Coast. Music, it seemed, did not afford me that. In any case, the day of departure arrived and I came to the assembly point more or less determined not to go. When I saw the preparations in progress my resolve grew and I told Buzzy that I simply could not bring myself to go. I chickened out.

The tour pulled out of San Francisco without me and I went on to work as a jewellery fabricator for the next fourteen years. As it turned out the tour was a great success, there were only a couple of altercations only one of which involved the use of potentially lethal weapons, (knives), and no one was hurt. They got to London, did their thing and dispersed. Buzzy went on to Paris where she lived and worked for the better part of a year.

So now with a day gig, (my first believe it or not), music became a weekend thing. I worked with some Texas friends of mine, Tary Owens, Jerry Lightfoot, Minor Wilson, Bob Brown, etc. Most of the ensembles we got together during this time, Stucco Duck for instance, never made it out of the garage. The only one to ever perform in public was a unit called "The Angel Band". We performed occasionally to little acclaim. The most interest we ever stirred came from The Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club a chapter of which showed up at one of our gigs and demanded that we change the name of our band. We instantly became "The Leapin' Lizards".

Gradually my Texas cohorts drifted back home and I, not having any contacts with other musicians in the Bay Area, lost touch with the performance side of music. I played guitar, wrote some songs and generally made music at home for my own amusement. Besides, around 1979 I fell in love again, this time forever. In 1983 the first baby arrived and in 1985 the second one came. My family responsibilities left little time for music and for ten years my guitar stayed stowed away in the closet under the stairs. It was not until the kids were grown and I retired in 2005 that my music career began to revive, but that's another story....

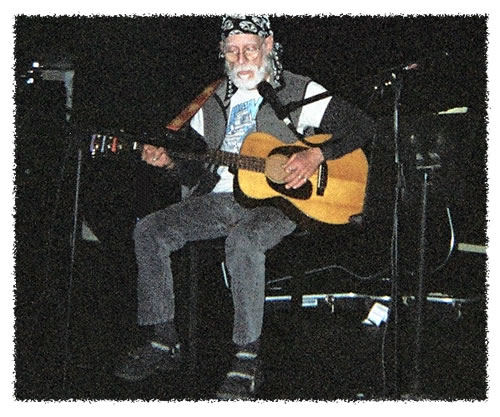

Interview feature and photo of Powell by Carlton Crutcher

Editing, artwork and layout: Phil McMullen

© terrascope online September 2009

With sincere thanks to Powell St John for his time, kindness and effort

See also our Conqueroo feature, here:

http://www.terrascope.co.uk/Features/Conqueroo_interview.htm